😰 The Pattern of Technology Panic

Technology panics also follow Gartner's hype curve, and in the worst case, they can initiate ill-considered bans and restrictions, writes Waldemar Ingdahl.

Share this story!

Hype cycle

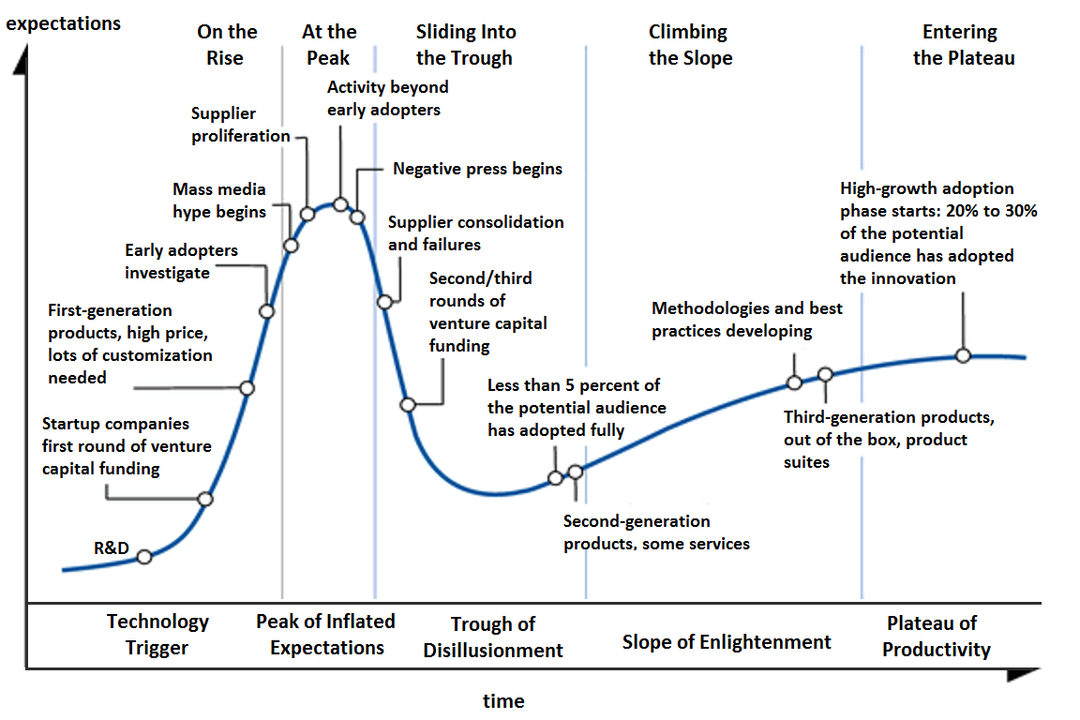

When new technology is introduced, it is perceived as groundbreaking before users learn to use it. The analytics company Gartner has formalized this sequence of events in its famous hype cycle.

The model from Gartner's hype cycle can also be used to formalize the fears society experiences when new technology is introduced, and how its risks are amplified and reinforced in public debate. In some cases, it can reach a technology panic.

Technology panic

In a technology panic, the technology is often described in an imagined future, completed form, and not in the initial versions available to the inventor, technicians, and early adopters.

There is an "industry of fear" today where various activist groups, politicians, and companies looking to sell their services, foundations, think tanks, opinion makers, officials, and even journalists and researchers fill different niches to drive alarm.

The reasons for pushing the alarm may vary, but often their strong priorities do not match those of the rest of society. They drive, for better or worse, the initial panic when few are even aware of the technology's existence.

Maximum panic curve

The panic curve reaches a maximum of hype, where there is no limit to the potential impact of the new technology. Strikingly often, the measures advocated at the peak of the panic curve are about general regulations of Big Tech rather than solving problems in specific situations.

At this stage, the alarm is gladly incorporated as part of more comprehensive narratives about how the fabric of society unravels. It drives the debate when otherwise a lack of public knowledge about technology can cause the momentum to fade. Youth become lazy, people's relationships fall apart, consumerism is rampant, and internal and external enemies seize power through the technology.

Over time, the warnings turn out to be exaggerated, not least because the technology was so new that most people were merely speculating about its capabilities. As the technology gets closer to users, it turns out not to be so dangerous, and soon everyone is using it. Users, manufacturers, and legislators address misuse, not the technology itself.

Initiating bans

Alarms and warnings can provoke early bans and restrictions, often on insufficient grounds.

Technology panics have a cumulative effect, especially if politicians want to put the cart before the horse with broad regulations. It is easy to become a little more scared each time a technology panic occurs, particularly if one does not perceive the debate's resolution at the end of the curve.

Users' perceptions can become so negative that the technology is stopped, as when users were shamed away from using Google's augmented reality glasses, Google Glass, or the technology is not used to its full potential even if it was not so dangerous.

Today, technology is rarely built for users to adapt or repair it themselves. Manufacturers often consider it better if the technology is closed. However, closed technology does not give a sense of control, making it difficult for users to assess how reliable the manufacturers can be, which in turn makes it harder to appreciate the value of the technology.

It is in tangible, individual intrusions that privacy advocates and legislators can make a difference. Social norms often prevent uses that are possible but unwanted. Regulations should give individual users control over their data.

Real privacy and control are a consequence of personal responsibility, and we should be suspicious of those who claim that ordinary users cannot be entrusted with that responsibility.

Waldemar Ingdahl

Originally published on Medium (in Swedish)

By becoming a premium supporter, you help in the creation and sharing of fact-based optimistic news all over the world.