🧠 Why are people so pessimistic about the future? Part 3 - our own brains

Our brains are on high alert when it comes to perceived danger. That was great thousands of years ago, but today the world is much less dangerous, and now our instinct makes us pessimistic.

Share this story!

In the first two parts of this series, we have seen how a lack of knowledge about the progress of humanity and the negative bias in media, makes people pessimistic about the future. But we also have our own brains working against us.

Availability heuristic, or bias, it’s called in psychology.

"We base our sense of risk and danger on anecdotes and images that are available from memory."

Says Steven Pinker, who, in addition to writing books on world development, is also a professor of psychology at Harvard.

This mental shortcut is used to quickly evaluate a situation. The problem arises when these anecdotes or images in our memory don’t match reality.

There are plenty of examples of availability bias with serious consequences. For example, doctors who have recently experienced an illness are more likely to make that diagnosis, even if facts point in a different direction.

Another more positive example is awards, at least for those who win them. Herbert Simon won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1978 and realized that the best way to win awards was to win awards:

“I soon learned that one wins awards mainly for winning awards: an example of what Bob Merton calls the Matthew Effect. Once one becomes sufficiently well known, one's name surfaces as soon as an award committee assembles."

Simon won a dozen big awards and was named an honorary doctor from no less than four universities.

Strong mental pictures

For a large part of my life, whenever someone mentioned Africa, or I read or saw "Africa" somewhere, my thoughts were drawn to the images I saw as a child. Poverty, children with swollen bellies, flies crawling on their faces.

When I began to become aware that there was a world outside of my own little bubble, there were famines in Ethiopia and other parts of Africa on the news. It affected me so strongly and the reporting was so extensive that the images were etched into my memory. So deeply that they stayed with me for decades.

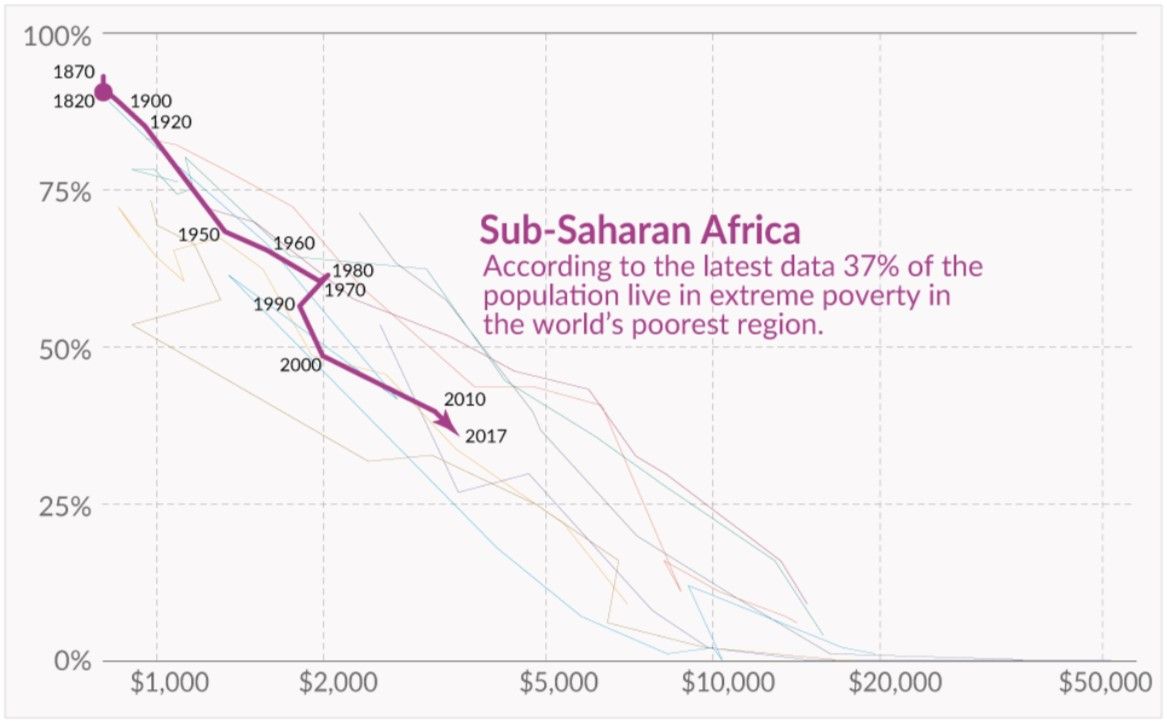

Since then, I have learned new facts about Africa:

- Extreme poverty has decreased dramatically.

- Life expectancy has increased from 37 years to 62 years since 1950.

- GDP per person has increased by about 25 percent since 1990.

Africa is still the poorest and most vulnerable continent, but there has been significant progress.

My old images of Africa have finally been replaced by others. Now, I think primarily of the African startup entrepreneurs I have met. Those who speak optimistically about how they are leapfrogging into the future. Instead of building a copper network for telephony, they skipped it and went straight to mobile phones. In the same way, they can skip development stages and move more quickly into the future.

But it took several years of seeing other images for the old ones to be replaced.

When we are fed daily with negative news, it is easy to believe that they represent reality. Especially about things that are really awful, which may affect us deeply. Against that kind of emotion, facts are fighting a losing battle.

“People tend to assess the relative importance of issues by the ease with which they are retrieved from memory — and this is largely determined by the extent of media coverage.”

Daniel Kahneman in his book Thinking Fast and Slow.

We are extra alert to perceived danger

Our brains are trained by evolution to be extra attentive when something could be dangerous. That was not so bad 150,000 years ago. If someone in your group had seen tigers in the distance, and now you think you see some movement in a bush nearby, just going over there and checking it out was of course a pretty stupid idea. Once upon a time, that was vital information, but now we live in a much safer world.

Hans Rosling writes in Factfulness:

“We need to learn to control our drama intake. Uncontrolled, our appetite for the dramatic goes too far, prevents us from seeing the world as it is, and leads us terribly astray.”

You can compare this to sugar intake. In the old world, it was a good idea to eat all the sugar you came across. For who knows when the next chance would come? There was no risk back then to consume too much sugar. So our bodies rewarded us when we found sugar and told us to eat everything we could. Our bodies still cling to that belief, but in a society with an excess of sugar, it is no longer a very good idea.

The dramatic, negative news is like sugar for us. Our brains suck it in because it thinks it’s good for our chance of survival. It has not yet adapted to a world where the dangers are much smaller than just a few hundred years ago.

We must learn to live in a new way. Hans Rosling again:

“Factfulness, like a healthy diet and regular exercise, can and should become part of your daily life."

Mathias Sundin

Editor-in-Chief

By becoming a premium supporter, you help in the creation and sharing of fact-based optimistic news all over the world.