🚢 How a box and a truck driver made the world smaller and the global economy bigger

Loading a medium-sized ship with loose cargo cost $5.86 per ton in 1956. If you instead used containers for the cargo, the cost dropped to 16 cents. This breakthrough dramatically changed the world in the second half of the 20th century.

Share this story!

📣🌊

A ship's horn is powerful. Imagine if thousands of ships sounded their horns at the same time.

At 11:30 a.m. Eastern Standard Time on May 30, 2001, ship horns sounded on all container ships around the world.

At the same time, the funeral for truck driver Malcom MacLean was taking place. The powerful sound rolling over the waves was to honor him.

Few people had a greater impact on the 20th century and our current time than Malcom MacLean.

The truck driver who changed the world

North Carolina was a major tobacco producer in the 1930s, and as a teenager, MacLean started driving a truck and transporting tobacco barrels. Over time, he built a successful transport company.

Back then, the logistics industry was heavily regulated with fixed prices on different transport routes. To make money, it was crucial to cut costs, which MacLean excelled at.

In this context, he began to consider whether it might be better to transport trucks by ship over certain distances. The initial idea was to place the entire trailer on the ship, but he soon discarded that since the undercarriage and wheels took up too much space.

Instead, he packed goods into containers and lifted them onboard. The container could be moved directly from the truck to the ship, and then directly from the ship to another truck upon arrival.

On April 22, 1956, in front of a hundred dignitaries, the world's first container ship was loaded with 58 containers, and in an instant, transport costs dropped dramatically.

Loading a medium-sized ship with loose cargo cost $5.86 per ton in 1956. Using containers instead reduced the cost to 16 cents, a 97 percent reduction.

MacLean's crucial insight

MacLean didn't invent the container. They already existed in various forms around the world. His revolutionary insight was that a logistics company's job wasn't to drive trucks or ships, but to transport goods. An obvious fact today, but MacLean was ahead of everyone else in his thinking in the 1950s, writes Marc Levinson in the book "The Box."

MacLean envisioned more than just container ships; he saw the bigger picture. Container ports with efficient loading and unloading to and from trucks and trains. This meant that a container could be packed and sealed at one location, driven by truck, loaded onto a ship, sail thousands of miles, transferred to a train, driven hundreds of miles, transferred to another truck, driven a few more miles, and arrive anywhere in the world just a few weeks later – without ever being opened.

Before this system, goods were loaded and unloaded one by one. One box, one sack, one item at a time in a slow and inefficient process.

While loading a container was a massive leap forward in the 50s, it was still slow compared to today. When MacLean's guests watched the loading in 1956, it took seven minutes to load one container. In today's fastest ports in Asia, it takes 27 seconds. Hence, 15 containers can be loaded in the time it took to load one back then.

The "Ideal X" was the world's first container ship. It was a tanker from World War II that MacLean converted. It could hold 58 containers. Today, the largest container ships can hold over 24,000 containers.

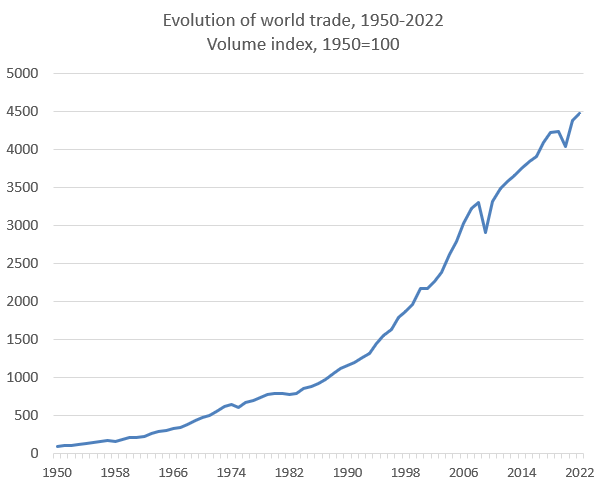

Before the container system, transporting goods was so expensive that international trade was limited. Since the 1950s, it has increased more than forty-fold. Not only because of containers, of course, but they have been a significant factor. About half of the world's total trade in goods is carried by container ships.

Huge consequences

The implications are too numerous to list here, but one result was the emergence of just-in-time production. Instead of maintaining large inventories, the manufacturing industry could operate much more efficiently. This enabled the success stories of Toyota and other Japanese companies, which in turn transformed manufacturing worldwide.

Not all consequences have been positive; trade and goods, for instance, contribute to greenhouse gas emissions. However, there's one overwhelmingly positive effect:

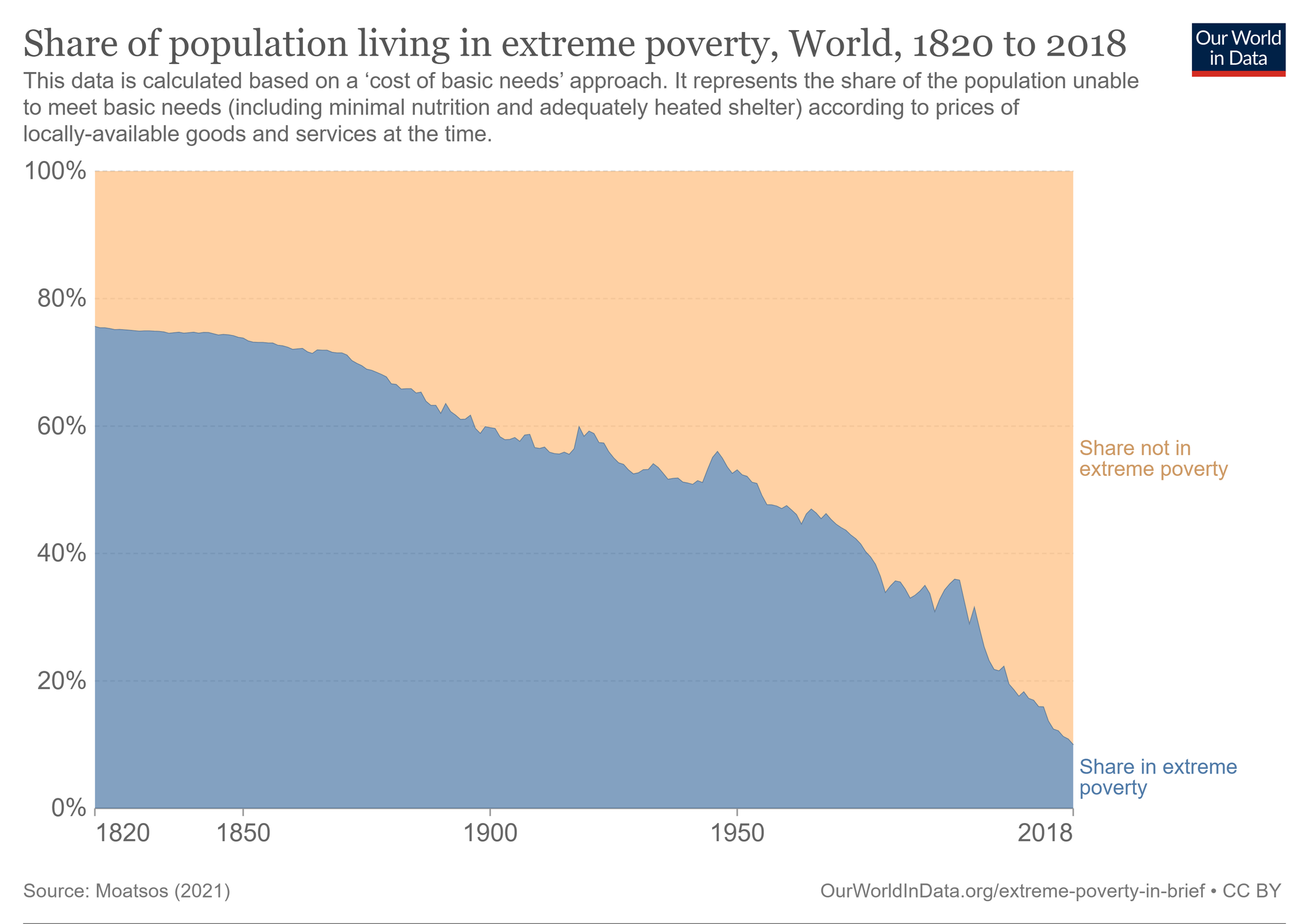

The largest container traffic is between East Asia and North America, with China recently becoming dominant. Most of the wealth in recent years has been generated in East Asia. Without container traffic and the surge in trade, over a billion people wouldn't have been lifted out of extreme poverty over the last three decades.

Trade and containers aren't solely responsible for this significant progress, but without them, it wouldn't have been possible on such a scale, so quickly. Hundreds of millions of people would likely still live in extreme poverty without container traffic.

Like all technological advancements, it also brings troubles. However, these problems can be solved. As David Deutsch writes in "Optimism, Pessimism, and Cynicism":

"Every solution creates new problems. But they can be better problems. Lesser evils. More and greater delights."

For that, we blow our horns. 📣

Mathias Sundin

Den arge optimisten

A book about containers might sound boring, but The Box is incredibly interesting.

By becoming a premium supporter, you help in the creation and sharing of fact-based optimistic news all over the world.